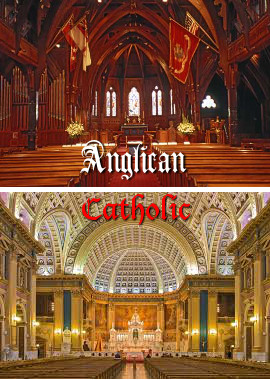

No, Anglicans are not basically Catholics. So what’s the difference?

Some time ago when I publicly commented that I could easily consider “going Anglican,” one of the comments I got was from a Catholic, telling me that I would have come “half-way home.” Since then as many of you know, I have gone Anglican and when I have told people about it, I’ve heard remarks suggesting that some people really aren’t sure if there’s a difference between Catholics and Anglicans. I’ve had people ask me things like: Don’t Anglicans venerate statues of Mary? Don’t they have confessionals? Don’t they believe in Purgatory? The answer to these questions is no, but I know that there are people out there asking these and similar questions.

In spite of my respect for some of the intellectual traditions represented within the Roman Catholic Church1, I could not in good conscience return to it because I am unable to affirm some of its fairly important teachings. For that reason I don’t want people thinking that I’m basically Catholic but not quite, so I wanted to put together a hopefully fairly succinct explanation of how Anglicanism is different from Roman Catholicism. I hope that it will not be received as something written against the Roman Catholic Church, but simply as an explanation of how one Christian tradition differs from another.

“Anglican Theology” vs “The theology that Anglicans hold”

There is a range of theology and values among people within the Anglican Church here in New Zealand and around the world, but that does not mean that there is equally a range of Anglican theology.

When I say “Anglicans believe…” or “Catholics believe…” of course there’s an easy objection to make: “But I know some Catholics who don’t believe that,” or “but I’m Anglican and I don’t believe that.” I understand that it can be offensive to be told that the group with which you associate “believes” or “values” things that you do not personally believe or value. It’s certainly not my intention to offend you or to tell you that you’re not a “real” Anglican. I know that there is a range of theology and values among people within the Anglican Church here in New Zealand and around the world, but, and I cannot emphasise this enough, that does not mean that there is equally a range of Anglican theology. When I talk about Anglican theology (and I will sometimes do this by saying “Anglicans believe…”) I am not talking about what all people who happen to be Anglican happen to believe. If that were the case then I would be wrong in virtually everything I say here. If that were the case, then I could not even say “Anglicans believe that Jesus was raised from the dead,” because you can find somebody who is a member of an Anglican Church who does not believe this (the same is true of Catholics, Lutherans, Presbyterians and so on). Instead I am talking about Anglicanism as a Church defined confessionally and historically. That is, I am talking about the history and statements of faith of the Anglican Church. Let me say again for emphasis: Even though, among Anglicans, there is considerable doctrinal diversity, there is not a corresponding range of Anglican beliefs. Not all Anglicans – even committed and involved Anglicans – know what historic Anglicanism teaches, and certainly not every Anglican believes all of it.

I might sometimes use specific Anglican people as examples (I am writing this introduction before writing the meat of this, so I say “might” rather than “will”), but on the whole my interest is in historic Anglican theology. So where do you start if you want a solid overview of historic Anglican theology? As far as historic written statements of faith go, the Reformed / Presbyterian Churches have the Westminster Confession and Catechism, along with less widely used documents in the Anglo-American world like the Heidelberg Catechism and the Belgic Confession. Lutherans have the Augsburg Confession. Roman Catholics have the statements of numerous councils and various documents issued by Popes: Constitutions, Bulls and Encyclicals (not all of which have the same type of authority in theory, but which in practice are embraced by the Church), but perhaps above all the voluminous Catechism of the Catholic Church. The works that historically define Anglican teaching are contained in two main works: The Book of Common Prayer and the Articles of Religion (commonly called the “Thirty-Nine Articles”). In the sixteenth century the Books of Homilies were also produced, which set out Christian doctrine and also call the reader to a holy life (you can get this book in pdf format via Google Books). The Thirty-Nine Articles refer the reader to the Homilies for further explanation (for example, on the doctrine of justification). Some of the material in the Books is reactionary in nature. This is not a negative feature, I only mean that the purpose of some of this material was to explain differences between the Anglican Church and the Roman Catholic Church in terms of belief and practice and hence to explain why Anglicans are not Roman Catholic. Also, some of the material has a local purpose, while other parts reflect societal custom. There are references to the princes, and when the Homily on the State of Holy Matrimony calls a man to love his wife, it refers to her as “her that is set in the next roome beside thee” (unlike the wyfe of that author, my wyfe certainly dost sleepe in the same roome as I).

History is best learned from history books, rather than from anti-Protestant polemics.

It’s important first of all to understand that Anglicanism and the English Reformation more generally was a theological reform. One of the myths that persists to this day (at least among some anti-Protestant apologists and probably among fans of the humorously named History Channel) is that the real difference, or at least the main one historically, between the English Protestants and Roman Catholics is divorce. Henry VIII wanted to divorce his wife but the Pope said no. So Henry started a new religion and Anglicans popped into existence (there were no other reasons for Reform as far as English Christians were concerned, you see). This is a story to be told right after “everyone in Columbus’ day thought the earth was flat” and “Religion is at war with science.” It is simply not true. The truth is that English Protestantism had precedent. Theological Reform was already underway and the Reformation in England was like the breaking of a dam, letting loose a torrent of renewal that had become pent-up. From John Wycliffe in the thirteenth century to the great martyr William Tyndale in the sixteenth, dissent from Rome – dissent grounded not in politics or disputes about marriage but grounded in Scripture and usually coming from those who, unlike much of the populace, knew Scripture very well (Wycliffe and Tyndale were Bible translators) – was alive and well in England. The Church of England provided – and still provides – a place for that Evangelical faith to be expressed.

But how is that faith different from the Roman Catholicism from which it distanced itself?

1 Authority, Scripture and Tradition

The theological reforms of the English Protestants (and their predecessors) were reforms derived from Scripture, which implied a fundamentally different approach to authority from that of Rome. The teachings of the Church are reformable, and Scripture has a teaching authority over the Church because Scripture is inspired by God. If you delve into English history, however, you’ll see that before the Reformation there had always been a rocky relationship between the Church in England and Rome. Allegiances being determined by a political decision were certainly not new with Henry VIII. His decision to split from Rome, you might even say, was an act of taking back an independence that had existed in years gone by. But politics aside, we cannot understand the Reformation in England (or anywhere) without seeing the basic question of authority as being crucial.

The Articles contain the following statement on the sufficiency of Scripture: “Holy Scripture contains all things necessary to salvation: so that whatever is not read therein, nor may be proved thereby, is not to be required of any man, that it should be believed as an article of the Faith, or be thought requisite or necessary to salvation.” So while the Church of Rome might declare to be de fide2 such things as divine simplicity or even relatively novel historical claims such as the bodily assumption of Mary (novel when it was declared, if not today), Anglicans simply leave such questions open to investigation. Scripture certainly does not make these claims so they can hardly be called necessary to the faith, and whether or not we believe them can simply be left as a matter of whether or not we are persuaded that there is good enough evidence for them.

The Anglican affirmation that the Scripture stands alone, without peer in authority and is sufficient for instruction in the faith, was no novelty. Instead it was the perpetuation of an ancient school of Christian thought. Many theologians (bishops, in fact) among the Church Fathers have expressed the same conviction. Basil the Great held that in principle all instruction for a righteous life could be derived from Scripture and the help of the Holy Spirit:

Enjoying as you do the consolation of the Holy Scriptures, you stand in need neither of my assistance nor of that of anybody else to help you comprehend your duty. You have the all-sufficient counsel and guidance of the Holy Spirit to lead you to what is right.3

Of course, Basil did offer his assistance even in telling people that in principle Scripture and the Spirit supplied all that we strictly need. Like Anglicans, Basil had a great love of tradition, but only where he believed that the tradition was derived from the Apostolic tradition that we find preserved in Scripture. Speaking of the Trinity, he says: “But we do not rest only on the fact that such is the tradition of the Fathers; for they too followed the sense of Scripture, and started from the evidence which, a few sentences back, I deduced from Scripture and laid before you.”4

Anglicans cannot accept a doctrine only on the grounds that it is taught by the Church. Instead they say with Gregory of Nyssa:

We are not entitled to such licence, I mean that of affirming what we please; we make the Holy Scriptures the rule and the measure of every tenet; we necessarily fix our eyes upon that, and approve that alone which may be made to harmonize with the intention of those writings.5

Anglicans agree with Augustine that “among the things that are plainly laid down in Scripture are to be found all matters that concern faith and the manner of life.”6

“We make the Holy Scriptures the rule and the measure of every tenet.”

Gregory of Nyssa

This ancient Christian way of thinking about authority and doctrine finds clear expression within the Anglican Church, setting it apart from the Roman Catholic view in which the Church has the authority to infallibly declare doctrine as binding on the Church, even when it is not expressed in Scripture. Article 20 expresses the contrary Anglican view of Church Authority: “although the Church be a witness and a keeper of Holy Writ, yet, as it ought not to decree any thing against the same, so besides the same ought it not to enforce any thing to be believed for necessity of Salvation.” The Church has no authority to decree anything against Scripture, nor does it have the authority to enforce anything as necessary when Scripture does not teach it.

This is not the only ancient Christian view regarding Scripture to find re-expression in the Anglican Church. Anglicans regard the biblical canon to consist of 66 books, rather than the longer canon used by Rome consisting of 73 books. It’s a surprisingly common claim in ecclesiastical polemics that the Church always used the Bible that included the Deuterocanonical books (books included by Catholics but not Protestants) and then one day along came the Protestants and took some books out. As I’ve demonstrated elsewhere, this is not true. Dating back to the earliest times and including such people as Melito of Sardis (died in c. AD 180), Origen (died in AD 254), Athanasius (died in AD 373), and Jerome (died in AD 420), along with the Christian communities that looked up to these teachers, there was an ancient and unbroken tradition of Christians using the Hebrew Canon of the Old Testament, resulting in a biblical canon of 66 books. In fact there was never a truly ecumenical Council that declared the larger body of books to be canonical, because the first attempt to do so was not until the Council of Florence in 1440, which was well after the schism between Eastern and Western Churches, and it was after the predecessors of the Reformation like John Wycliffe too – people who were continuing in the ancient tradition of using the 66 books of Scripture. Florence was really only a specifically Roman Catholic Council, binding on those within the now Roman Catholic Church in an age where historical orthodoxy was no longer tied to being in the same Church as those in Rome.

In its approach to teaching authority as well as the makeup of Scripture, then, Anglicanism is different from Roman Catholicism.

2 Justification

Historically, Anglicanism has taken the view that we are counted as righteous in God’s sight only because of the merit of Christ, through faith and not because of any good works that we have done (see Article eleven). Although we are justified by faith and not works, as Article twelve adds, good works “spring out necessarily of a true and lively Faith.”

Exactly how much this differs from a Roman Catholic view of justification is a matter of some discussion, especially since Vatican II.

Exactly how much this differs from a Roman Catholic view of justification is a matter of some discussion, especially since Vatican II in the early 1960s, a council that saw the Roman Catholic Church begin to take a much friendlier approach to Protestants, in appearances at least. Better late than never! But the key difference, historically, has been that in a Roman Catholic view, our justification is a process brought about by infused righteousness, referring to the process of actually becoming more holy and righteousness in our lives. The cause of this infused righteousness is the reception of the sacraments of the Church. In an Anglican view, although it is certainly true that God’s work in our lives brings about sanctification, a process of becoming more holy, we are completely safe by virtue of being treated as righteous on the basis of our faith in him. Sanctification is evidence of justification. In simplified terms, Anglicans see a holy life as the result or fruit of our salvation, and not part of the basis of our salvation.

In much more recent times, N T Wright, a prominent Anglican theologian, has come along and disturbed the waters, forging a theology of justification (one that he takes to be biblical) that does not fit neatly into traditional Catholic or Protestant schemes. In his view, our justification involves us being acquitted by virtue of our sin being imputed to Christ crucified (as in Anglican theology), but our acquittal now is in anticipation of our future acquittal on the day of judgement in light of our future state of righteousness. It is fair to say, however, that Wright’s work represents a self-conscious departure from historic Anglican teaching – teaching that is, let us remember, open to further reform if there are biblical grounds for that reform.

3 The Eucharist / Mass

At the centre of Roman Catholic worship is the Mass, in which, Catholics believe, the bread and wine of the Eucharist are actually transformed into the person of Jesus Christ; his body, soul and divinity (a doctrine called transubstantiation), so that it is entirely proper to literally worship the Eucharist, because it is Jesus Christ Himself.

Anglicans do not believe this. Articles 28-30 give a summary of the historic Anglican view of the Lord’s Supper. Article 28 rejects transubstantiation as “repugnant” and as the source of many superstitions (likely referring to practices like the procession and adoration of the Eucharist, something that simply has no early Church witness in its favour). Instead, those who take the bread and wine in faith receive Christ in a “heavenly and spiritual manner.” The sacrament is effective, but not because of anything in the substance of the bread and wine – only through the obedience in taking part and the faith of one who partakes.

Unlike somebody who believes in transubstantiation, Anglicans believe that since the benefit of the Lord’s Supper is spiritual and received through faith, you do not receive Christ simply because you eat and drink it. Christ is not the bread and wine, after all. Article 29 declares that the “wicked” who take part in the Lord’s Supper do not gain any benefit from it since they are “void of a lively faith.” Instead they really store up condemnation because they unworthily receive the sign of so great a thing, namely the body and blood of Christ. But it would be a mistake to lump Anglicans in with anyone who says that taking communion is just a memorial and offers no spiritual benefit. Here is where the Anglicans agree with the Reformed view that we certainly do “feed on Christ” in communion, but not because Christ comes down into the bread and wine. Instead, as we take part, God lifts us up to himself.7

On a related matter, Article 24 adds, “It is a thing plainly repugnant to the Word of God, and the custom of the Primitive Church to have public Prayer in the Church, or to minister the Sacraments, in a tongue not understanded of the people.” This prohibition may have been drawing on St Paul’s teaching to the Corinthians and was certainly a reaction against the practice of Latin Mass, where the Mass is carried out in Latin and the congregation (for the most part) could not understand what was being said.

4 A married priesthood

Roman Catholic priests, as a rule, are forbidden from marrying. In the “Eastern rite” there are some married men who become priests, but in the Latin Rite – the priests with which most of us are familiar – this is the rule: No marriage. When it comes to priesthood in general, Anglicans hold to the doctrine of the priesthood of the believer. Priests do not offer sacrifices on our behalf and they do not offer Christ in the Eucharist. But in spite of this important theological difference, they still use the word “priest” to refer to ministers in the church. There is nothing in Scripture calling ministers to abstain from marriage, “therefore it is lawful for them, as for all other Christian men, to marry at their own discretion, as they shall judge the same to serve better to godliness” (Article 32). This was no novelty, but an ancient practice. You may recall, if British history is your thing, that Saint Patrick, missionary to the British Isles, had a father who was the son of a priest (you may also recall that St Peter was a married man).

5 Purgatory and Prayers for the Dead

Anglicans believe that you should take the opportunity to pray for a person now, in this life, while there is hope for a change of heart if need be.

The statement in Article 22 is negative, stating only what is not affirmed: “The Romish Doctrine concerning Purgatory, Pardons, Worshipping and Adoration, as well of Images as of Relics, and also Invocation of Saints, is a fond thing, vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God.”

But stated positively, Anglicans see this life as the opportunity for people to benefit from your prayer, which is really a call to urgency in prayer: Do it while there is life and hope. In the Catholic view, our prayers for the dead may benefit them if they are in purgatory, as we may accumulate merit for them, thereby shortening their stay in purgatory, ushering them into heaven sooner.

As the eighteen-year-old stood near the executioner’s block and addressed the watching crowd, she asked them “And now, good people, while I am alive, I pray you assist me with your prayers.”

This conviction – both in the value of prayer now and that it does not assist the dead – was reflected poignantly in the gracious manner in which Lady Jane Grey conducted herself at her execution under “Bloody Mary.” As the eighteen-year-old stood near the executioner’s block and addressed the watching crowd, she asked them “And now, good people, while I am alive, I pray you assist me with your prayers.”8 “While I am alive” was a phrase deliberately chosen for the purpose of affirming that this life is the time when we are in need of prayer. The Church stood to gain nothing, materially, by denying the existence of purgatory. Indeed belief in purgatory had been a source of income to the Roman Church, with relatives or friends of deceased people paying the Church for masses to be conducted for them. But the Church in England would not accept the doctrine of purgatory for the simple reason that it is not taught in Scripture.

6 Invoking Deceased Saints

The same Article that rejects purgatory also rejects the invocation of departed saints. If you hunt around the internet for Anglican perspectives on this, you’ll find a couple of things, along with some irony. You’ll find, on the one hand, Anglicans who happily quote the Articles and explain that historically this is one of the ways in which Anglicans differ from Roman Catholics. From an historical perspective, this is correct. On the other hand you’ll find some who might prefer the label “Anglo-Catholic” who see themselves as part of the Anglican community, but who nonetheless reject some of its historic teachings, and who say (misleadingly) “yes of course we Anglicans invoke departed saints and ask them to pray for us.” The irony is that the latter are dubbed (by some, at any rate) to be “high Anglican” or “High Church Anglicans.” That’s how the terminology has come to be used and I can’t help that, but it does seem strange that a movement that is less Anglican in terms of historical theology can be thought of as “high” Anglican. I nearly had a head explosion when I read the website of one such Church that defended the practice of praying to the saints and venerating their images, while having links on the website to articles in praise of saints like Thomas Cranmer and William Tyndale, Anglican saints who would have been completely horrified by what was being said!

If there are Anglicans who pray to departed saints, they certainly don’t do it on the basis of Anglican Theology.

One of the ways in which Thomas Cranmer reformed the liturgy, reflecting Anglican theology, was to remove all references to asking departed saints to intercede for us. In fact, while the Articles were still undergoing historical development, there was a time when there were forty-two of them (a list formulated under Edward VI), with article forty specifically denying soul sleep, in a statement very likely included because of the controversies with the Anabaptists at the time, a number of whom believed the doctrine of soul sleep (the view that the dead are unconscious until the resurrection). However, any opposition to the doctrine of soul sleep was removed from the articles under Elizabeth I. Soul sleep had gained something of a following (although not an official one) among British Protestants. Even before the term “Protestant” would have been meaningful, the doctrine was held by John Wycliffe. It was emphatically taught by William Tyndale and John Frith in the sixteenth century. In Scotland it was taught by George Wishart, tutor to John Knox. Since then there have been a number of Anglican thinkers to have held to either soul sleep or conditional immortality, both views (sometimes held together) that call into question the immortality of the soul. The articles do not require one to take a position on the nature of the soul or its state after death (possibly in part because the Church knows full well that there is a range of opinion within its ranks on the subject), but speaking for myself I think those Anglicans who embrace soul sleep are probably the most consistent with the Anglican tradition of maintaining that prayers only benefit the living.

In short, if there are Anglicans who pray to departed saints, they certainly don’t do it on the basis of Anglican Theology. In the liturgy used by Anglican Churches here in New Zealand, departed saints are mentioned, but only to say that we commend them into God’s hands, and we give thanks to God for the example they have set before us, asking that it may inspire us.

Summary

I’ve passed over some smaller differences, and I’ve stuck mostly to theological differences (so I’ve left differences in Church Government alone entirely). But the ones that I’ve covered are biggies: A different view of the Church and the authority of its traditions compared to Scripture, a different view of justification before God, a different view of communion – something central to both Catholic and Protestant worship – different practices in the lives of priests, different views on the existence of purgatory and a different approach to Saints who have died. All of these considered together represent some very important differences between Anglicanism and Roman Catholicism.

Of course it would be a mistake to think of Protestantism and Catholicism as opposites. At every eucharist service, Anglicans together affirm their faith with the words of the Nicene Creed, as do Roman Catholics (and many other Christian Churches). They have more in common than not. But Anglicanism is certainly not just an English version of Roman Catholicism and the differences between them are not small.

So while I am certainly catholic (a word that just means “universal,” emphasising the unity of the whole church), Anglicans are very different from Roman Catholics.

Glenn Peoples

- I use the term “Roman Catholic” in spite of the fact that some Roman Catholics dislike the term, although I do so without intending to offend. I use that term because in principle I prefer to verbally acknowledge the fact that a number of Church traditions value catholicity, and I regard Roman Catholicism as only one such branch. I am too catholic to suggest that all real catholic Christians are Roman Catholic. [↩]

- A doctrine that is declared de fide is deemed to be an essential part of the faith that must be believed and is hence not reformable. [↩]

- Letter 283 [↩]

- The Holy Spirit, chapter 7 [↩]

- On the Soul and the Resurrection [↩]

- On Christian Doctrine, Book 2 chapter 9. [↩]

- For an excellent example of the sorts of theological writings being produced by Anglican theologians at the time of the Reformation on the subject, see the work of the martyr Nicholas Ridley, A Brief Declaration of the Lord’s Supper [↩]

- Justin Taylor relates the account of Jane Grey’s death here. [↩]

P.O. Bamikole

Hey Glenn,

Thanks for this post. It was a good read, and the ECF quotes were new to me (thus more appreciated). I’ve been a reader for a bit over a year now, and after having read many of your older posts from years back, I was only a little surprised by your joining the Anglican communion. (The ‘little surprise’ was that you intend to remain a credobaptist but will fellowship with bebe-baptizing rogues). If you’re able, I’d love to learn more about Anglican church government, historical and present. I know that Hooker & co. ably defended episcopacy, but I don’t know what that defence consisted of. Also the many (on-going?) realignments in Anglican & Episcopal congregational life make the whole system hard to grasp. Whether you’d like to write on this, or point me to people who have – either would be appreciated. Thanks!

Thomas Nolen

I’m glad to see the promised myth-busting of Anglican origins, and I agree in large part.

One difficulty of criticizing the Anglican church is that it’s like poking holes in a sponge. Even if one disproved an Article of Religion (as I thought of attempting in response to this post), the Anglican church can just respond by shrugging its shoulders. However, there is a point which I could not shrug off and which helped push me away from Anglicanism. The Episcopalian church ordains women at all levels. I really wanted to believe that was OK so I could be in a comfortable agreement with the quickly growing majority of Protestants around me. But I couldn’t get over certain facts like the 12 being male. And this wasn’t like other issues where members of the Church could hold different positions and the Church can move on like normal. If certain ordained positions are indeed meant to be reserved for men (which Jesus seems to believe), then placing women in them is like putting the wrong type of cog in a machine; It will cease to function properly.

Here is a good presentation on the differences between Anglicanism and Orthodoxy from the perspective of an Orthodox Bishop in 1912 http://www.oodegr.com/english/oikoumenismos/Raphael_Brooklyn_Episcopalians.htm

I share this since I once considered the Anglican Church to sort of be a Western Version of the Orthodox Church.

James

The name for the comment above should be James since that is the name I go by (middle name). Apologies.

Blair

Thank you for posting this. My knowledge of both Anglicanism and Roman Catholicism is limited, and this is quite helpful.

I have a couple of questions. You wrote about Authority – does the Anglican Communion accept any of the seven Ecumenical Councils? The Carthaginian canon of 397AD was actually confirmed at Trullo in 692AD, which included without distinction the Deuterocanon.

With regard to the Eucharist, do Anglicans subscribe to “consubstantiation” – this notion that Christ hangs around the bread and wine like some sort of celestial mosquito? And would you agree that the Anglican notion is that the Eucharist is the Body and Blood of Christ through the pious act of the Christian taking it, rather than the material offered being in itself special?

Do you have any proof or evidence that Tyndale rejected veneration of Saints? Soul sleep would not necessarily imply that. The idea that one *shouldn’t* venerate Saints seems to me to play little part in Christian thought until the Protestant explosion of the 16th Century. Do you have any knowledge of the history of High Church Anglicanism that would suggest that it was something that started later, rather than simply a continuation of previous Catholic practice, while obviously rejecting the Latin innovations such as Papism, purgatory and indulgences so loathed by Protestants. I don’t know much about it so I would be interested.

James – are you Orthodox? There was definitely some dialogue in the last century between Anglicans and Orthodox, and High Church Anglicanism seems to be about as close to Orthodoxy as Western Christianity has gotten. But I think it all turned to custard when the C of E started ordaining women.

Glenn

Blair, I’m not clear on what you’re claiming about the canon. There was a council in Trullo from 680-681, namely the sixth ecumenical council, which did not affirm the Deuterocanon. But the council commonly called the “Council in Trullo” in 692 – and this looks like the one you are talking about – was not ecumenical. It was the “Quinisext” council, attended only by Eastern clergy. I’m not aware of anything in the Anglican confessions that would commit to the seven ecumenical councils, except insofar as they are reflected in the Anglican confessions (e.g. the Nicene Creed). Beyond that they would likely be authoritative in the sense that tradition, reason and experience are authoritative generally in helping us to understand Scripture.

No, Anglicans do not believe in consubstantiation. That’s the Lutheran view, and it does not involve a “celestial mosquito.” In constubstantiation, the body and blood of Christ are present, and so are the bread and wine. They exist together. And yes, in the Anglican view (which historically is the same as the Reformed view, actually), we feed on Christ in the Eucharist through faith, rather than by materially consuming the bread.

Tyndale certainly rejected the invocation of the saints, because he believed in soul sleep, which does necessarily mean that the departed saints cannot be invoked. So he would certainly have disagreed with those who said that we may pray to the saints and should venerate their images, which is what I said. The departed saints, in Tyndale’s view, cannot possibly hear us or intercede for us.

I am not intimately familiar with “high” Anglicanism, although it does seem to me to be a step back from the English Reformation towards Rome.

James

Blair, I am currently undergoing the Catechumen process! I talk a bit about it in my blog. That’s basically what I heard about Orthodox-Anglican dialogue.

Blair

James – do you have a link to your blog? The one your provided seems to be broken.

James

I missed a letter, this link should work.

James Hiddle

Nice article. It makes me want to join the Anglican Church. Are there any books out there that teach about Anglican Church/Theology that is along what you posted in this article?