I thought it was high time we had another “nuts and bolts” blog, part of a series where I unpack some of the basic terms and concepts used in either theology or philosophy. This time we’re in theological territory, looking at the question of what this thing called Liberal Theology (or “theological liberalism”) is.

As I’ve noted before when discussing the issue of inerrancy, Martin Luther said that the Bible made statements that weren’t correct about the number of people involved in battles. John Calvin said that the Bible made statements that weren’t correct about a bright star in the sky when Jesus was born. Charles Hodge* said that when it comes to truth and error, the Bible was like a marble building, where marble is truth and sand is not. Sure the building might contain the occasional speck of sand which isn’t marble, but we can still call it marble overall.

Now as I look around the world of conservative evangelicalism, I notice that nobody calls Luther, Calvin or Hodge a liberal (or at least, nobody that I am aware of). And yet for expressing this sort of thought about the Bible myself (namely that everything it teaches is true, but it contains incidental claims that are not factually correct), I’ve recently been called a theological liberal (albeit by a very small number of people whom I can count on the fingers one hand and still have a couple of fingers left over). Theological liberalism is the movement represented by the likes of John Shelby Spong, Lloyd Geering in New Zealand, or historically by folk like Rudolph Bultmann or Friedrich Schleiermacher. I wonder how these guys would feel at being lumped in with Calvin and Hodge?

Moving on to the issue of the afterlife, well known evangelical scholar John Stott claimed, on exegetical grounds, that the lost will one day be no more and that only those people who have eternal life in Christ will live forever. The same position was expressed by other evangelical authors like Michael Green, Philip Edgecumbe Hughes and John Wenham. The church father Arnobius of Sicca taught the same thing (this is just meant as a tiny list of examples).

And yet, for defending this same doctrine – on the basis of detailed exegesis of many parts of Scripture – I’ve been dubbed by one or two people in recent times a theological liberal. I wonder how John Spong would feel being told that he was in the same camp as John Stott!

Of course as many readers will see right away, something has gone askew here. All of this is just a case of confusion. Unfortunately there’s a tendency for some evangelicals (although fortunately not the majority) to think that their stance on any theological issue is the default conservative one (naturally!), and that if a person doesn’t hold their view then they must (obviously) hold a view that makes them a liberal. What’s on display when this happens is actually just historical ignorance of what theological liberalism actually is, combined with confusion over the difference between erroneous beliefs and a theologically liberal stance. As I said when I started the “nuts and bolts” series, rather than just getting frustrated at ignorance, it’s better to become part of the solution. So today I’ll be answering the questions: what is theological liberalism, and how is it distinguished from say, error or heresy?

Read More

Did you know that I’m an Apostle? It’s true! My ex sent me packing, and the word “apostle” in the Bible comes from a Greek word that means “sent one.” Don’t argue with the Bible, this is what the Greek means!

Did you know that I’m an Apostle? It’s true! My ex sent me packing, and the word “apostle” in the Bible comes from a Greek word that means “sent one.” Don’t argue with the Bible, this is what the Greek means!

In the Nuts and Bolts series I lay out some of the basic concepts thrown around in my areas of interest – philosophy, theology and biblical studies – and explain them for those unfamiliar with them.

In the Nuts and Bolts series I lay out some of the basic concepts thrown around in my areas of interest – philosophy, theology and biblical studies – and explain them for those unfamiliar with them.

I started the “Nuts and Bolts” series as a way of explaining some of the basic / common concepts in philosophy as well as theology at a fairly introductory level. Sometimes this is prompted by the realisation that online, often people refer to those concepts – even criticising or commending them – without actually having a firm grasp on them. It was an example like this that prompted me to start the series.

I started the “Nuts and Bolts” series as a way of explaining some of the basic / common concepts in philosophy as well as theology at a fairly introductory level. Sometimes this is prompted by the realisation that online, often people refer to those concepts – even criticising or commending them – without actually having a firm grasp on them. It was an example like this that prompted me to start the series. In the “Nuts and Bolts” series, I lay out some of the fundamental ideas and terms used in philosophy and theology for the lay person.

In the “Nuts and Bolts” series, I lay out some of the fundamental ideas and terms used in philosophy and theology for the lay person. In the “nuts and bolts” series, I explain and discuss some of the fundamental ideas in philosophy (and theology sometimes) that are taken for granted within the discipline, but which might not be very well known to ordinary human beings. This time the subject is ethical intuitionism (or moral intuitionism).

In the “nuts and bolts” series, I explain and discuss some of the fundamental ideas in philosophy (and theology sometimes) that are taken for granted within the discipline, but which might not be very well known to ordinary human beings. This time the subject is ethical intuitionism (or moral intuitionism).

In the “nuts and bolts” series, I explain and discuss some of the fundamental ideas in philosophy (and theology sometimes) that are taken for granted within the discipline, but which might not be very well known to ordinary human beings. This time the subject is nominalism.

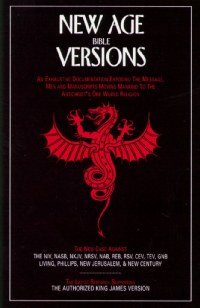

In the “nuts and bolts” series, I explain and discuss some of the fundamental ideas in philosophy (and theology sometimes) that are taken for granted within the discipline, but which might not be very well known to ordinary human beings. This time the subject is nominalism. I recently had an encounter that reminded me of the existence of the “King James Only” movement. Spend a few years intently engaged in serious scholarship in theology and biblical studies, and you could easily forget that the movement is even there, because it’s a movement that is not relevant to such study. You’ll never see a reference to the movement or any contributions from it – but it’s there, and now in the age of the internet it has an audience like never before.

I recently had an encounter that reminded me of the existence of the “King James Only” movement. Spend a few years intently engaged in serious scholarship in theology and biblical studies, and you could easily forget that the movement is even there, because it’s a movement that is not relevant to such study. You’ll never see a reference to the movement or any contributions from it – but it’s there, and now in the age of the internet it has an audience like never before.