The 4th of July is American Independence Day, on which Americans celebrate the signing of the Declaration of Independence (the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand is also interesting, but that’s for another time). It’s one of those days when revisionary political liberals sharpen their pencils and write letters to the editor to try to offset the natural effect that facts have on people. In other words, they attempt to convince people of things that aren’t so. When it comes to the Declaration of Independence, perhaps the major thing that secular liberals might want to do is to distract people from what the declaration says – especially all that stuff about God – and to remind people of the supposed fact that in a truly free nation, religion stays out of the public square. Reading the Declaration of Independence pushes any such thought well into the background:

The 4th of July is American Independence Day, on which Americans celebrate the signing of the Declaration of Independence (the Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand is also interesting, but that’s for another time). It’s one of those days when revisionary political liberals sharpen their pencils and write letters to the editor to try to offset the natural effect that facts have on people. In other words, they attempt to convince people of things that aren’t so. When it comes to the Declaration of Independence, perhaps the major thing that secular liberals might want to do is to distract people from what the declaration says – especially all that stuff about God – and to remind people of the supposed fact that in a truly free nation, religion stays out of the public square. Reading the Declaration of Independence pushes any such thought well into the background:

Consider the opening words of the Declaration:

When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bonds which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

The basis of human equality, along with the basis of human rights, is explicitly theological God bestows equal status and dignity upon human beings. From Abraham Lincoln to John F. Kennedy, these sentences have held a place of privilege in many political figures since the time they were written.

Some secular liberals, however, are honest. Yeah I know, try to subdue your shock. Within the literature on political philosophy and the issue of religion in the public square, I’ve found that – unlike the opinion pages of the local newspaper – there’s a tendency to actually deal with reality. Take Martha Nussbaum for example. She doesn’t try to re-write history. She accepts the facts of what the Declaration of Independence says, but she’s a secular liberal, so she does the honest thing: She denounces the declaration. In fact, since she realises that a thoroughgoing secular outlook has no way of defending the claim, made in the declaration, that all people are really equal, she declares that this too, along with the reference to God, makes the declaration unacceptable in a secular liberal democracy. I don’t like her ideas, but I love her honesty.1

Glenn Peoples

- Martha Nussbaum, “Political Objectivity,” New Literary History 32 (2001), 883-906, especially 896. [↩]

Scientism

Scientism A couple of times in recent history I’ve encountered Christians who have used the sentence “you’re going to be dead a lot longer than you’re going to be alive” as a way of referring to the fact that heaven (or hell) is forever.

A couple of times in recent history I’ve encountered Christians who have used the sentence “you’re going to be dead a lot longer than you’re going to be alive” as a way of referring to the fact that heaven (or hell) is forever.

I’m in the process of writing the next podcast episode on Alvin Plantinga and his arguments around the idea of belief in God as a properly basic belief. In it, I’m clearly on Plantinga’s side, and I think his work in that area represents a crucial contribution to philosophy of religion (and to epistemology).

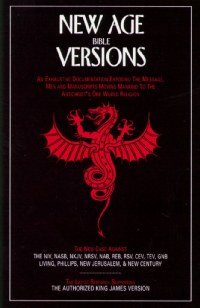

I’m in the process of writing the next podcast episode on Alvin Plantinga and his arguments around the idea of belief in God as a properly basic belief. In it, I’m clearly on Plantinga’s side, and I think his work in that area represents a crucial contribution to philosophy of religion (and to epistemology). I recently had an encounter that reminded me of the existence of the “King James Only” movement. Spend a few years intently engaged in serious scholarship in theology and biblical studies, and you could easily forget that the movement is even there, because it’s a movement that is not relevant to such study. You’ll never see a reference to the movement or any contributions from it – but it’s there, and now in the age of the internet it has an audience like never before.

I recently had an encounter that reminded me of the existence of the “King James Only” movement. Spend a few years intently engaged in serious scholarship in theology and biblical studies, and you could easily forget that the movement is even there, because it’s a movement that is not relevant to such study. You’ll never see a reference to the movement or any contributions from it – but it’s there, and now in the age of the internet it has an audience like never before. This is the third and final instalment in a short series of blog entries on the discredited but “popular on the internet” belief that not only is Christianity false, but Jesus of Nazareth never even existed at all. In the first part, I looked briefly at the unacceptable and controlling bias when demanding that only sources from outside the New Testament be regarded as historical evidence. In part two I looked at some historical sources that give further credibility to the historicity of the person behind the Christian faith, namely Jesus himself. Those sources, while clearly useful and such that they cannot simply be dismissed, were arguably of minor significance, often due to questions of when they were written.

This is the third and final instalment in a short series of blog entries on the discredited but “popular on the internet” belief that not only is Christianity false, but Jesus of Nazareth never even existed at all. In the first part, I looked briefly at the unacceptable and controlling bias when demanding that only sources from outside the New Testament be regarded as historical evidence. In part two I looked at some historical sources that give further credibility to the historicity of the person behind the Christian faith, namely Jesus himself. Those sources, while clearly useful and such that they cannot simply be dismissed, were arguably of minor significance, often due to questions of when they were written.