Souls are on the way out. Not just in our culture or in science, where some Christians may suspect “naturalism” as the culprit, but souls are on the way out of our Bibles. This is because of the ways in which our translations are getting better at conveying what was originally intended. In the King James Version of the Bible, translated in 1611 and the mainstay for Protestants until the 20th century, the English word “soul” appears 537 times. The New American Bible (1986) features the word 171 times, the NIV (1984) features it just 139 times, the NRSV (1989) features it 252 times, but that includes the Deuterocanonical books, and even the ESV (2001), which hearkens back to older more literal translations, features the word just 281 times. The difference is not because of any difference in the manuscripts that these versions are using but because of a better understanding of what the Hebrew and Greek words actually mean.

Category: theological anthropology Page 1 of 3

Conditional immortality as a view of human persons, although biblical, comes with an emotional price. I wanted to share some thoughts about fear and doubt, and the roles they play in how we respond to what Scripture teaches about human nature, death, and destiny.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

What difference does it make if the Bible teaches we are physical creatures, rather than dual body-soul beings? How does that impact on anything else we believe as Christians? From gender identity to mental health more generally, to salvation, the way we view human nature has a profound impact.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Did Jesus say that believers would never ever die, indicating that even when their bodies die, they will live on with him in glory? You might have heard that, but what if he meant something different, promising that we would be spared the fate of disappearing into death forever?

I get some resistance to the biblical concept that human beings are frail and mortal, “dust of the earth,” that we return to the dust when we die, and that there’s no heavenly life to be had while our bodies lay in the grave awaiting the resurrection of the dead. Sometimes people even pit Bible verses against this biblical idea. One verse at a time, I think we can see that these objections fail, and the overall clear biblical portrait of human nature and death remains intact.

One of those objections comes from a particular interpretation of Jesus’ saying after raising Lazarus from the dead in John 11:25-26:

“I am the resurrection and the life. Whoever believes in me, even though he dies, will live, and whoever lives and believes in me will never die.”

Never die. That gives pause to some people when they consider my view that immortality is received at the resurrection and that the dead are really dead in the grave, not living on as immortal souls. They wonder if this claim by Jesus must mean that if we live and believe in him now, we cannot lie dead in the grave without our souls living on in glory, because we will “never die.” It’s a good question to ponder, but there’s already a reasonable response to this worry, quite apart from the observation I’ll make soon. Jesus is here talking about those who live the new life that he has just referred to: Whoever believes in me, even though he dies, will live – that is, via the resurrection. So when Jesus goes on to say “whoever lives and believes in me will never die,” he’s talking about the life of immortality after the resurrection.

You can only believe in purgatory if you hold a substance dualist view of human beings.

Purgatory is a place that exists according to Roman Catholic Theology, and a number of people who are not Roman Catholic believe in it, too. In Catholic theology, it is a place where you go after death if you are not yet ready for heaven, so that you can receive punishments for the venial sins (the less serious sins, as opposed to mortal sins) that have not yet been dealt with in this life. As Thomas Aquinas put it,

[I]f the debt of punishment is not paid in full after the stain of sin has been washed away by contrition, nor again are venial sins always removed when mortal sins are remitted, and if justice demands that sin be set in order by due punishment, it follows that one who after contrition for his fault and after being absolved, dies before making due satisfaction, is punished after this life. Wherefore those who deny Purgatory speak against the justice of God: for which reason such a statement is erroneous and contrary to faith.

Outside of this historical Catholic understanding of purgatory, others have suggested, not that people need to be punished, but rather that they simply need to be fully sanctified (made holy) before reaching their final state in heaven. Jerry Walls defends this view in his book Purgatory: The Logic of Total Transformation. In public conversations, Dr Walls has remarked that while no doubt the sinful human desire is to have total transformation all at once, the reality is that sanctification is a process that takes time, hence purgatory.

I do not believe in purgatory, but I will not here argue that purgatory does not exist. Instead, I will just make one observation: To believe in purgatory presupposes mind-body substance dualism.

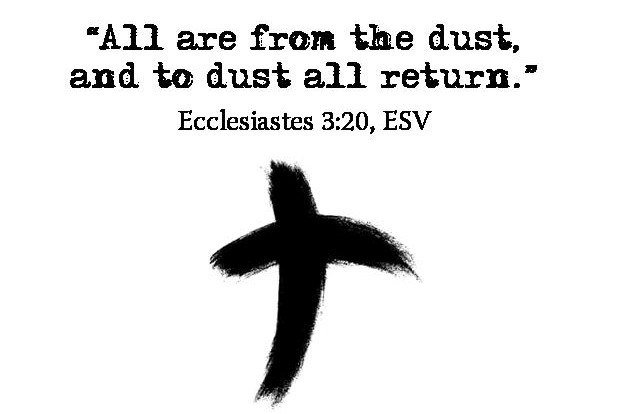

We just got back from taking our kids to their first Ash Wednesday service. Ash Wednesday kicks off the season of Lent, a time where we examine ourselves with a repentant heart, confessing our sins and reminding ourselves of God’s mercy. Many people give something up for lent and the practice of fasting during Lent is common, so that people can take their focus off their needs and pleasures and focus on being made right with God.

During the Ash Wednesday service, participants are marked on the forehead with a cross. Tonight the prayer just before the marking with ash really stood out to me:

Loving God, you created us from the dust of the earth; may these ashes be for us a sign of our penitence and mortality, and a reminder that only by the cross do we receive eternal life.

What a simple reality. The prayer wasn’t burdened down with the language that we sometimes use to describe these truths, terminology like “physicalism,” “conditional immortality” or “annihilationism.” One of the frustrating things (but of course not the only frustrating thing) when Christians deny these biblical truths and talk about the immortality of the soul or about everybody living forever (it’s just a question of where they live) is that we have to come up with terminology to describe these positions.

This prayer, though, is a perfect example of how something like “annihilationism” or “conditional immortality” is ideally expressed, with the straightforward, unadorned claims of the Bible. We are mortal, made from the earth (or from stardust as some scientists like to say), we are dust and to dust we will return. We should have no default expectation of living forever, and it is only through Christ that we can have eternal life. Call that “conditional immortality” if you like, but it’s just the Christian Gospel.

Glenn Peoples

Might it be true that the gender of some people’s souls doesn’t match the sex of their bodies?

In the ever-driven politics of the language of gender, the word “cisgender” has been forged. Without harping on too much about it, it’s a word that, in my view, has been created in part to destabilise the notion of “normal” as far as gender goes, so that what most of us took to be normal until now can be spoken about as simply one condition among the others. To be “cisgender” is to have physical makeup – including chromosomes but especially including sex organs – so that by examining your physical structure, a person can tell whether or not your gender is male or female.

I’m delighted to announce that in December 2014 the Ashgate Research Companion to Theological Anthropology will be published, featuring a chapter from me called “The Mortal God.” The chapter is about how a doctrine of the incarnation might look coupled with a materialist view of human beings. Theological anthropology is about coming up with a view of human persons from a decidedly theological point of view, although there is a natural overlap with philosophy of mind, philosophy of religion, theology and biblical studies. Questions about bodies, minds, souls, spirits, life, death, eternity and more are tackled in this sizeable piece of scholarship.

I’m delighted to announce that in December 2014 the Ashgate Research Companion to Theological Anthropology will be published, featuring a chapter from me called “The Mortal God.” The chapter is about how a doctrine of the incarnation might look coupled with a materialist view of human beings. Theological anthropology is about coming up with a view of human persons from a decidedly theological point of view, although there is a natural overlap with philosophy of mind, philosophy of religion, theology and biblical studies. Questions about bodies, minds, souls, spirits, life, death, eternity and more are tackled in this sizeable piece of scholarship.

Here’s the synopsis:

Does the Bible actually teach that souls live on when the body dies? Short story: no.

Does the Bible actually teach that souls live on when the body dies? Short story: no.

In part 1 of this series I looked at what the Bible does say about the mind-body question. You should read that before you read this post. In short, in Scripture there’s a fairly clear portrait of human beings as physical and mortal, returning to the earth when we die, and depending on the resurrection of the dead for any future life beyond the grave. The familiar view of human beings as immaterial souls that inhabit physical bodies and live on when the body dies is not one supported in the Bible.

But is it really that simple? The evidence we saw last time was surprisingly clear, but still, some Christian readers of Scripture are resistant to this message. There are some passages in the Bible – although not many – that seem to some Christians to suppose that actually human beings do not die when their bodies die, but they actually live on in non-material form. Their souls don’t die. Some passages of the Bible, some people think, teach dualism because they teach that the soul outlives the body.

This might surprise some people, but embracing a biblical worldview gives us reasons to be mind-body materialists rather than dualists.

I first rejected mind-body dualism not because of any sort of scientific scepticism but because of what I started to see in the Bible when I started looking.1 For what it’s worth, I think other Christians should do the same.

- Specifically, I mean substance dualism, a view most clearly represented by the French philosopher René Descartes, or in classical thought by Plato. Materialism as a view of human beings is compatible with property dualism, with emergentism or with hylemorphism (in which a human being, like any other creature, is a compound of matter and form), in spite of the fact that the word dualism is used to describe each. The key is that these are views where the only substance involved is a physical substance. [↩]